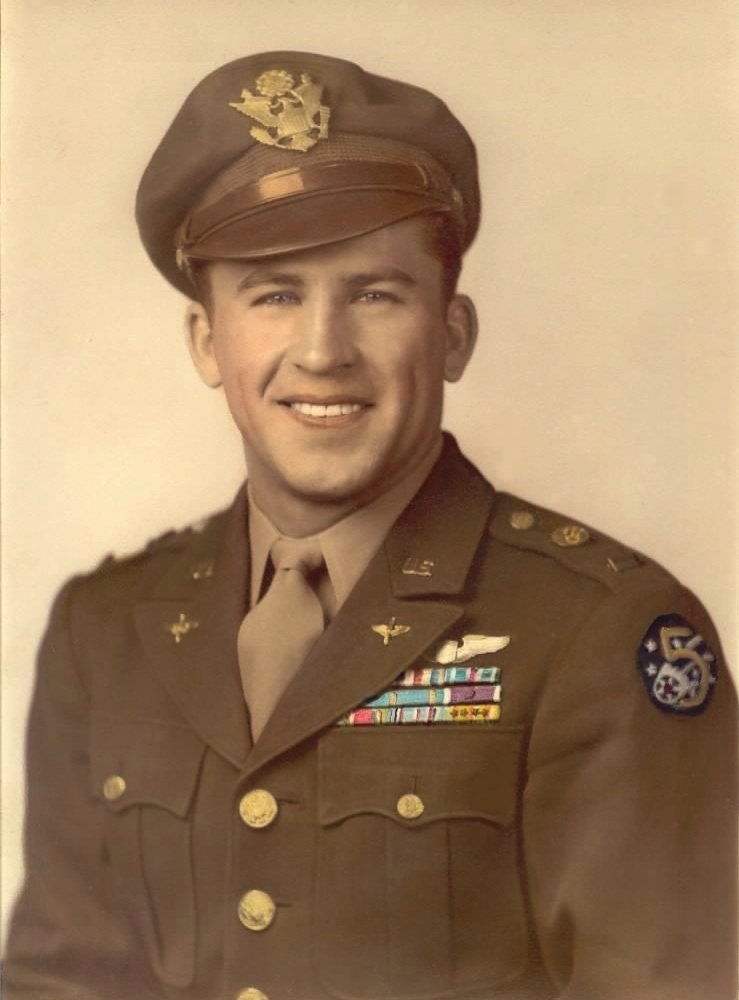

Lt. Leonard Thomas Duval served with the 90th Attack Squadron 3rd Bombardment Group , based in Hollandia, Dutch New Guinea. He was a member of the 3rd Bombardment Group, and piloted an A-20. He was shot down twice, captured by the Japanese, and twice escaped into the jungle before being rescued. Lt. Duval was honored for the actions he took in New Guinea before being shot down, and for those taken during his escapes. He was awarded the Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart with Oak Cluster, WWII Victory Medal, American Campaign Medal, Air Medal, Asiatic Campaign Medal, a POW Medal, and later (for the Berlin Airlift) a Medal for Humane Action. Captain Leonard Duval retired from the Air Force in 1951.

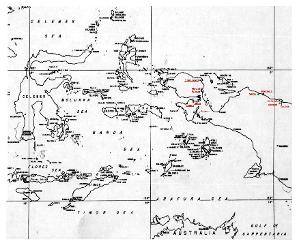

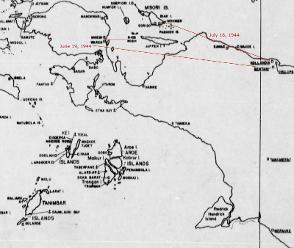

These maps show the area that the 3rd Attack Group was operating in while based at Hollandia. The second map shows the flight paths approximately which Lt. Duval was flying on June 19 & July 16, 1944. It should be noted that according to the accounting below Lt. Kenneth Lindsay was the pilot on the July 16, 1944 flight with Lt. Duval as a passenger. There doesn't appear to be a MACR for the July 16 flight and the June 19 account is tied in with that of Albert F. Burke of the 89th Attack Squadron who went MIA on the same day. There doesn't appear to be any record of the other passengers on July 16 flight.

Though he lives a quiet life in the Baker area now, Leonard "Tony" Duval's memories of World War II in the Pacific include harrowing tales of plane crashes, capture and escape from enemy hands. "We had our guns firing and the bomb bay doors open. We dropped our bombs where we were supposed to, and we were going away," Duval said. "When the Japs heard us coming, they turned everything up (anti-aircraft guns), and we had to fly through that."

That was the first time Duval was shot from the sky. Duval, 72, and his wife, Betty, both natives of Morgan City, now live quietly on Blackwater Road. But 50 years ago, in June 1944, Duval was a member of the 90th Attack Squadron Third Bomber Group of the Fifth Air Force, based at Hollandia, Dutch New Guinea. He was 21 and in the midst of World War II in the Southwest Pacific.

A member of the Grim Reapers, Duval piloted an A-20 Attack Bomber Grim Reaper. The planes, with a large skeleton holding a scythe painted along the nose of the aircraft, were aptly named. The bombers had 14 50-caliber machine guns mounted in the nose and wings and about 3,000 pounds in bombs. A gunner had two 50-caliber machine guns to cover the rest of the aircraft. The aircraft trembled when all machine guns were fired.

"We approached the mountain, skimming the tree tops. On the other side of the mountain was Moemi Airdrome." The Japanese air base was well defended.

"I dropped all my bombs and got hit in the open bomb bay (an opening in the belly of the plane)," said Duval. "It went off inside the bomb bay between me and the gunner in back. Another shell hit and took part of my cockpit away and cut the safety harness that held me.

"Pieces of shrapnel got in there and pierced my left arm and right leg. The hit took off part of the right engine," said Duval, leaving the burden of the plane on the left engine. Duval received a broken nose in the crash. His gunner was killed.

After his rescue, Duval was brought back to Hollandia to the base hospital, where a doctor straightened his broken nose and tended the other wounds. Awarded the Purple Heart, Duval was given time for rest and recuperation at Sydney, Australia.

He returned to duty at Hollandia early on the morning of July 16, less than a month after being shot down. Duval was assigned another bomber and flew to Biak Island to pick it up with another pilot, Lt. Lindsey , and two other crew members. Duval lay in the life raft compartment behind Lindsey and the two crew members sat in the midsection behind the bomb bay.

As they flew over the northern coast line of New Guineau toward Biak, Lindsey saw a Japanese gun emplacement, banked his aircraft, circled back and straffed the emplacement.

Japanese artillery was turned upward for the attack and a shell hit the tail of the A-20. Lindsey, flying below tree top level, was now trying to get the plane over the tree tops. He clipped the trees and headed out to sea. The aircraft went out over the sea and about 300 feet up, flipped over on its back and went nose first into four feet of water, 300 yards from shore. It broke into three pieces.

"When the tail broke off the two crew chiefs were thrown out," Duval said, and Lindsey slammed into the front of the cockpit. "I got out on the wing, helped Lindsey out of the cockpit, but he was hurt very badly. I placed him on the wing. I knew there were Japs there and they were wading into the water. There were 12 to 15 of them shooting at us," said Duval .

Duval emptied three clips from a .45-caliber pistol at the Japanese soldiers to keep them away but ran out of ammunition. The first capture and escape, "There was no place to go but to sea or to the beach. So I held my hands up, and they came on," he said. He threw the empty pistol into the sea. "When we got to the beach, I saw the bodies of the two crew chiefs on the edge of the beach, and the Japanese had taken all their clothes. They were killed in the crash. They made me pick Lindsey up and carry him piggyback to their camp.

"No pilots had ever been taken alive there. I took off my wings and his and threw them in the grass. Lindsey was crushed in the cockpit." He had a broken leg, a broken arm, a broken jaw, a back injury, and he was scalped, Duval said.

"When we got to camp, they took our watches and crash bracelets and insignia. Now, I had my high school ring on my finger, and it wouldn't come off. But one of them pulled his knife out, so I figured I'd give him the damn ring," Duval said with a laugh. Duval and Lindsey were tied with their hands behind them with their parachute cords. Lindsey was kept by a fire, and Duval was tied to a stake beneath the leader's hut.

"Later on that night, I knew Lindsey was suffering and in great pain. I heard a pistol shot. I knew what happened. But I knew he wasn't suffering anymore," Duval said. "I thanked God for his (the Japanese soldier's) compassion.

"Earlier in the evening, the leader had boiled some rice in the shack, and he poured the hot water through a crack in the floor on me, and it was falling on my head. I leaned forward, and it went on down my back on the parachute cord. It got wet and gooey. I pulled on the cord until I got my hands loose. I waited until everything was quiet and got the rope off my feet and just crawled off in the jungle," said Duval.

He found a large stump, crawled into it and slept. At daylight, Duval headed back the way he had come, narrowly evading several patrols before nightfall. After crossing several sloughs, he came to a river which swept him out toward sea when he tried to cross. Duval walked upstream about 300 yards, took a running start and dove into the river, emerging on a sandy point across the river, soaking wet, cold and exhausted.

Captured again. "After I rested, I headed for the jungle, where I was surrounded by Jap soldiers with rifles and bayonets," Duval said. "I still had my clothes, which they stripped off me. The leader got my fleece-lined Australian flying boots. I was bound hand and foot with my hands behind back while they excitedly asked questions."

Duval gave only his name, rank and serial number, which angered the leader. The leader kicked Duval, then leaned over and spat on him. Duval kicked the leader. He became enraged and struck Duval on the forehead with his sword. Fortunately, it was not sharp. "When I came, to I was lying on my stomach on the beach with my face in the sand. They grabbed my feet and dragged me, face down up the beach. I was thrown in a hole in the sand, covered with palm fronds and left there. I waited at least an hour and kicked off the fronds. I was in a small shallow boat which was buried in the sand."

Duval rolled out of the boat and searched around until he found a tin can with a serrated lid and cut himself free. Knowing the Japanese soldiers were returning, Duval went back into the jungle.

By now, Duval had infections in both feet, thorns from the jungle stuck into his body, and a large gash in his forehead from the eyebrows to his hairline from the Japanese leader's sword.

"Next morning, I found a strip of cloth and bound the wound on my head. I climbed a tree to see my direction and headed out, without clothes or shoes. The mosquitoes were vicious, and the swamp was full of leaches," Duval said.

All day was spent avoiding patrols and Japanese camps and wounded Japanese on the trails. Many wore only a G-string, and Duval used his bandage as a G-string. He was so dirty, blackened and sunburned that he walked past the Japanese on the trails, and they never looked at him twice. "They thought I was a Japanese," he said. He would soak in the warm ocean to help his wounds. It was the only way he could walk by then on feet the size of footballs.

One Japanese sniper fired a number of shots at Duval, so he eventually went back into the deep, smelly swamp water and got lost. "I came out of the swamp miles and miles away and climbed a series of small mountains. I found a Jap officer's shack on top of a cliff and Japs in the village below. There were several gun emplacements dug into the cliff," he said.

"I was still running around without any clothes, so I went in there, and he had some canvas pants. I put them on. I couldn't put shoes on because I had coral poison and jungle poison in my feet. All I could find I could use was a pith helmet and a swagger stick. All Jap officers had a swagger stick," Duval said. Walks 103 miles. Duval was to find later he had walked 103 miles in five days and four nights, not including the times he went in circles.

"By this time, I was feeling pretty cocky," he said. On the cliff, Duval heard airplanes in the distance - A-20s. "I realized they were coming to where I was. When I saw them I knew what they were going to do. I hauled butt far as I could from that cliff. Three abreast, each firing 14 50s, and they blew the whole side of the mountain off," said Duval.

When the bombing and straffing were done, the A-20s left, and Duval went into the village. "They were all gone. There wasn't a soul in sight. So I just walked through the village. It was just clear. There wasn't anything there," Duval chuckled.

He walked out into the ocean and removed the Japanese officer's canvas pants rubbing against the thorns imbedded in his skin and the places where the mosquitoes and leeches had bitten him.

"I saw a destroyer off shore. I was howling and waving at them, and they started shooting at me. Then, I realized they weren't shooting at me, they were shooting at the gun emplacements," Duval said. He went into a cave until the shooting stopped and returned to the beach.

"I was walking along there, no shoes, no drawers. I had a pith helmet and a swagger stick. All of a sudden, from behind a big log, these five GIs stood up, about 100 feet away. I tried to holler at them, but no sound came out. I tried to say 'Hi, I'm American.' But I hadn't talked in five days and not a sound came out." They started to shoot Duval but thought he might be a native.

When the American soldiers discovered Duval was an American pilot, a sergeant offered Duval his underwear so he would have some clothing.

"They got me a cup of coffee, and some soup. I had been dreaming every night about a cup of coffee. By the time I was finished, I was so stiff I couldn't move. They put me on a stretcher in a truck. They sent six soldiers with me," Duval said, overcome with emotion at the memory. Duval was visited while at the hospital by a general and the 31st Division Intelligence staff and debriefed. He gave them detailed information on gun emplacements, troop movements and locations of the enemy.

After a stay in a military hospital, Duval was transferred back to the United States, where he lectured other pilots and taught them they could escape. For Duval's actions in New Guinea, prior to being shot down and for actions during his escape, he was awarded the Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart with Oak Cluster, World War II Victory Medal, American Campaign medal, Air Medal, Asiatic Campaign Medal, and later for the Berlin Airlift a Medal for Humane Action. A POW medal is pending.

Duval retired with an honorable discharge from the U.S. Air Force on Aug. 31, 1951, with physical disabilities resulting from injuries received in June and July 1944.

Wheelchair bound today, Duval can still laugh about some of his experiences in the Southwest Pacific.

And he can still weep.

RECOLLECTIONS OF RICHARD V. SAUNDERS

In June 1944 the 3rd Group was stationed on Lake Sentani strip inland from Hollandia in Dutch New Guinea. Two pilots from 90 Sqn, Lt. 'Tony Duval and Lt. Kenneth W Lindsay (Ken had been an artist with Disney pre war and some of his cartoons appear in 'The Reapers Harvest'.) were ordered to fly to Biak Island and return with a repaired plane from there to base. I was posted to Australia a couple of weeks after that flight sad in the knowledge that both had been listed MIA. In August while on leave in Sydney I went to a favourite drinking spot for the 3rd Group in the Hotel Australia hoping to catch up with someone from the Group. Who should be there but Tony Duval. After thanking me for assisting him survive in the jungle through my survival courses he related the following story.

Tony and Ken left Sentani heading for Biak when they suddenly experienced engine trouble and had to ditch close to shore. While assisting a badly wounded Ken they were taken prisoner by a party of Japs. Probably because Ken was beyond their care they killed him. Tony was trussed up and dumped under the old raised native hut where the Japs lived. Tony later untied his leg rope and headed off but was recaptured and reroped. Later that night he broke free again and escaped. He travelled eastward acquiring Jap clothes and boots en route. Tony was a short person with dark hair and a yellowish flesh from the Atebrin we all took for malaria. For three weeks Tony made his way toward US lines living off the jungle plants for food and water. One night he slept under a big tree and on waking next morning found a Jap asleep on the other side. He did meet an odd Jap along the way and simply grunted when spoken to. He poured sand down gun barrels, discarded vehicle distributor rotor blades and generally made a nuisance of himself without being detected. He eventually heard American voices nearby after the three weeks on the run so he hid behind a good tree trunk and proceeded to swear and cuss until the US troops realized that he, despite his appearance, was in fact a US soldier. Tony, of course, was welcomed back to his old unit and in August after recovering his health was given R & R leave to Sydney.

That is as true an account as Tony gave me that I can now recall.

When the 3rd Group moved from Dobadura to Nadzab the Lt. whom I only remember as Tony Duval occupied the tent next to the one I lived in at that time. My parents, when rationing allowed, often sent me packets of tea for they were aware that I preferred tea to coffee. So when time etc permitted I would brew myself a cup of tea. Tony, when he realized that I was brewing, would come and share a cup with me and because of this he and I became good friends with much talking together over a 'cuppa'. In addition I made, what we in Australia call a 'Coolgardie safe'. This is simply a primitive water evaporation cabinet used in the 'outback', where power was absent, to keep butter etc from melting. So when I finished building this cooling system it became a place to keep chocolate firm and of course Tony was an early and constant user. Whilst I do not recall Tony being with us at Dobadura he must have been for it was there that I conducted my courses in 'jungle survival' for the crews. If you read my story on Tony's escape from the Japs you will see that he used such course to survive. Therefore he must have been in Dobadura too.

Richard V. Saunders