Charley Mayo, usually known to his comrades in the 89th Bomb Squadron

as “Chuck” or “Charles”, was born in the southern town of Greenville,

North Carolina. He was the second oldest in our large family of 12 boys

and 2 girls. We siblings always looked forward to Charley’s letters

and his visits home. He always led such an interesting and fascinating

life. The stories included in this write-up are ones he shared with us,

either by mail or during visits home. We always sat quietly by (rare

for a family of 14!), listened, and absorbed every story he told. We

admired Charley and, like everyone else, we were mesmerized by his

considerate, kind, easy-going, and enjoyable personality.

Charley developed an intense love of flying while attending NC State

College in Raleigh, North Carolina. Outside school hours, he

successfully completed the basic and advanced courses offered by the

Civil Pilot Training Program at the Raleigh airport. There was no

doubt in his mind - Charley definitely wanted to be a pilot. When the U.S. military finally began accepting new pilots, he immediately enlisted in the US Army Air Corp at Fort Bragg, NC. He

enlisted right after college graduation, on May 31, 1941, as an Aviation

Cadet.

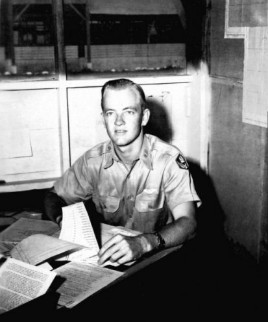

Charley completed primary training at Hicks Field, Fort Worth, Texas, and Curtis Field, Brady, Texas. He was then assigned Advanced Training at Brooks Field in San Antonio. Charley graduated from their pilot school in January 1942. He had become a Second Lt. and had earned his pilot wings. He completed his advanced military training at Meridian, Mississippi. Both pictures below were made during training.

Charley enjoyed basic training. The advanced flying skills he had accomplished in the Civil Pilot program paid off. They afforded him a distinct advantage in his military training. In basic training, he and his flight instructor often took off and stumped together, performing extremely low level flying. Once, during training, Charley was assigned to photograph a bridge. He flew over the bridge and photographed it. We’re told that he then flew under the bridge upside down and photographed the underside of the bridge. When Charley turned in his assignment, his instructor told him that they were excellent pictures, but please don’t ever fly upside down under that bridge again!

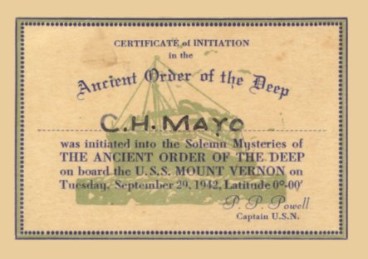

In the fall of 1942, Charley received his assignment for duty in the Asian-Pacific Campaign as a fighter pilot. At the last minute, the Air Corp decided to transport those pilots on the USS Mount Vernon, docked in San Francisco, instead of by plane. The Mount Vernon, a former cruise ship, had been hastily stripped of its entire interior and converted to wartime use. Since these pilots were last minute additions to the ship, Charley said they had to take whatever spaces were left available. (Charley didn’t ever complain, but we think he was politely saying “the worst on the ship.”) According to Mother’s Bible, Charley departed for overseas on September 24, 1942. He informed his family that he was leaving his 1937 Hudson Terraplane at his girlfriend’s house in Meridian, Mississippi and that we could pick it up and use it until his return.

We have been able to ascertain that Charley had 3 gunners that flew missions with him.

S/Sgt. Wade W. Wright / S/Sgt. James E. Luttrell / S/Sgt. Sylvester Silva

In November 1942, the 89th Squadron flew many combat missions into the Japanese occupied Buna area. During one of those missions, Charley realized that a comrade’s plane was disabled. The plane and crew had landed in water in enemy territory. To his dismay, Charley could see that the crew’s life rafts had gotten away from them, and they were struggling to reach those rafts. The survivors were trying hard, but just couldn’t seem to manage to get to their rafts. Charley flew low, beside the rafts, and blew them a long distance, back toward his comrades. As soon as he circled around and returned, though, he observed that the wind had taken the life rafts away again, before they could be reached. Suddenly, Charley saw a hidden U. S. spy dart from behind a tree, grab a boat, speed across the water, and quickly rescue his comrades. Charley felt immeasurable relief.

On December 3, 1942, Charley was wounded while bombing and strafing the heavily defended airdrome at Buna. He made 6 runs under heavy enemy fire, determined to destroy an enemy antiaircraft site. He suffered a shattered cockpit, twisted control wheels, a bullet through a fuel tank and a sheared radio headset, severing communication with his gunner. A machine gun bullet that exploded on the instrument panel had injured his left hand, face, and neck. Charley managed to land the damaged plane safely, but spent the next month recuperating in a hospital in Australia. He was very concerned that his gunner had also been injured, losing two fingers during combat. When the plane bucked during combat, the gun track had swung around and, unfortunately, detached the gunner’s two fingers.

Ironically, when Charley flew the above mission in the Buna Campaign, his own plane, Rebel Rocket, was suffering low oil pressure. Hence, Charley had flown unnamed plane A-20 #39421, in that Buna mission. That same plane, A-20 #39421, damaged in Charley’s flight, was written off a week and a half later. It was totally damaged while being flown by another 89th pilot. Michael Claringbould states that the wings of this unnamed plane were salvageable, though, and that these wings were mounted on Little Hellion to become The Steak and Eggs Special. The two photos below show that unnamed plane, A-20 #39421. Since Charley and his gunner were both injured, neither are shown in the two photos. The details of the plane are not discernable, but Charley stated that on the first photo, machine gun holes were visible in the top of the cockpit window and that on the second photo, machine gun hits were visible on the opposite side of the plane, with ack-ack hits behind the propeller.

On March 3, 1943, Charley participated in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. When the 89th Squadron approached the large convoy of Japanese vessels, Charley was flying Rebel Rocket on the extreme right of the formation. He observed an unexpected pile-up of planes, blocking his originally intended target. Charley said there was no way he was going to carry those 2 bombs back to base – they were earmarked for the Japanese. He sought permission - and proceeded to fly off to the right to attack a distant enemy vessel. Of course this meant Charley was flying alone and had no protection. Flying at mast height, he strafed the Japanese transport ship, dropped his 2 bombs, scoring two hits and then returned safely to base. Charley’s bravery was just one small example of the heroism of the Fifth Air Force that day.

We cannot identify the date, but the next event occurred about the time

the 89th Squadron had a problem with the safety of their night security

guards who watched over their A-20s. (We understand the safety problem

was solved by positioning the guards around the planes such that each

guard was within sight of the next guard - and could see behind his

comrade’s back). Anyway, the 89th Squadron decided they needed to make

peace and improve their relations with the tribe of headhunters in the

area. The rest of Charley’s story follows.

The 89th Squadron, for the goal of better relations, made plans to send a small envoy of soldiers far back into the jungle to visit the chief of the headhunters. Charley was among the small group assigned that task. The group traveled by Jeep down a narrow jungle trail, guided by local natives. They were led deeper and deeper into the jungle. They had no idea what to expect when they arrived – or even if they were safe in their environment. They finally arrived at the hut and were led inside. To their utter shock, the very first thing they noticed was that the walls of the chief’s hut were wallpapered with pages of Life magazines. A pin-up of Betty Grable, current actress, hung on the wall. The envoy decided that, evidently, the missionaries present in New Guinea earlier had visited the chief and left copies of the American magazine. But to see Life magazine in a remote hut, in the middle of the jungle, on the remote island of New Guinea, so far from home, was mind-boggling to Charley and his comrades.

On April 12, 1943, a major Japanese raid on Port Moresby occurred, creating devastating fuel fires. Most of the 89th Squadron had taken cover. Charley related that he and several comrades happened to be in the area of the fuel fire at the time, whereas the fire department was located in a different area. Charley and his comrades observed the plane’s aviation fuel barrels ablaze and exploding –and knew the 89th’s ability for combat was in peril. They didn’t wait for anyone. Charley directed and they immediately started up a bulldozer and began pushing key barrels aside to contain the fire. Charley explained to his family that they could detect which barrels were nearly ready to explode because the barrels always started bulging before exploding. Their object was to avoid the exploding barrels, yet try to break the line of fire so the fire could not reach the remaining tanks. Despite knowing that another Japanese attack could occur at any time and that their job was perilous, this small group persevered until the fire department arrived. They never asked for or received any recognition whatsoever, but they knew that they had saved an appreciable amount of fuel by their early effort.

On May 15, 1943, Charley, along with pilots Donald Good, leader, Turner Messick, Jack Taylor, John Conn, Joe Moore, Hayes Brown, William Neel, and Wade Wright swept their A-20s down on the Japanese airdrome at Lae and caught the Japanese completely by surprise. Four Zeroes and 6 or 7 Japanese bombers were parked out in the open; they were all completely destroyed in that attack. The Japanese were taken by such surprise that they didn’t even fire back. Some of the Japanese even fled for the woods.

One month later, on June 16th or 18th (records differ), 1943, Charley’s plane, Rebel Rocket was crashed. It joined the ranks of the many 89th planes that had to be written off. The mechanic was taxiing the plane from its parking area, down the runway, and toward the maintenance area for routine work. He states that the brakes failed. The plane crashed into a ditch. Rebel Rocket was damaged beyond repair.

Charley later told our family about participating in laying a smokescreen to conceal parachutists in a major military operation in Markham Valley on Sept. 5, 1943. Charley’s plane had been chosen to lead the A-20’s in laying that smokescreen. Charley knew that there was zero room for error. He made sure he was right there while his engineer prepared his plane. He double-checked to be sure everything was a-okay for that operation. He was taking no chances. General Kenney, General Douglas McArthur, and other VIPs observed the operation from planes high above. Afterward, Charley was so pleased that his plane had performed beautifully and that the 89th’s part of the operation had gone off like clockwork. He told us to check Life magazine (October 25, 1943) to view the laying of this smokescreen and to learn details of the operation. The following photo of the smokescreen appeared on page 30 of that issue of Life, followed by a write-up of the entire operation.

By January 1944, Charley believed the battle in New Guinea had pretty well been won. He had been awarded the Purple Heart, Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross with Oak Leaf Cluster, the Air Medal, Presidential Unit Citation, and Asiatic-Pacific Campaign with a Silver and a Bronze Service Star. He had definitely pushed his luck. Although he was told he’d be promoted to Major if he stayed on, Charley reached his conclusion: he would push his luck no further and go home to some good food.

When Charley arrived stateside, he brought home the keen flying skills that he and his buddies in the 89th had learned and practiced in New Guinea. We had no telephone on the farm in North Carolina at that time. Hence, on visits home, Charley couldn’t call from the airport on arrival for a pick up. Instead, he announced his arrival at our farm with his airplane. He used the same techniques he had used during the war. He would swoop down very low across the back field, bump up over the tobacco barns, come down again across the big field behind the house, and then soar upward at a steep angle to avoid the trees in the woods ahead of him. By then we always knew that Charley was home and wanted someone to come to the airport and pick him up. Even the small fry in the family happily recognized his arrival. Several years later, Charley explained to his family that he never would have attempted those low level flights on the farm had he not just come back from continuous low altitude flying in New Guinea. Charley’s

initial assignment, stateside, was as a test pilot at Wright Field in

Dayton, Ohio, assessing the suitability of various planes for low level

flying. He then served as a B-25 flight instructor and later as P-61,

Black Widow Night Fighter instructor, both at Shaw Air Force Base, South

Carolina. In

March 1947, when the 414th Night Fighter Squadron and their P-61s were

transferred from South Carolina to Rio Hato, Panama, Charley went with

them. By October 1947, he was temporarily assigned as fighter

controller at the Quarry Heights control center in Panama.

Within a few months, Charley was assigned to the U.S. Air Force Mission to Argentina, located in Buenos Aires. This was part of the Caribbean Air Command, with headquarters at Albrook Air Force Base, Panama. While in Buenos Aires, Charley was attached to the U. S. Embassy. Charley arranged ground transportation and made routine flights to Headquarters in Panama for business and supplies. He often flew Ambassador Bruce’s visiting dignitaries on sightseeing trips of Argentina, to visit Iguazu Falls, to hunting trips in nearby areas, etc.

In February 1949, the Commander of a special U. S. squadron, also

located in Buenos Aires, wanted to make a trip to Panama. He needed to

have routine work done on a C-47, take his pregnant wife to her doctor

there, and be back in time for his new Commanding General’s reception on

February 18th in Buenos Aires. No co-pilot in his group was available

for that specific time frame, so he asked CAIR to loan him Charley to

serve as his co-pilot.

Sadly, Charley’s life - and the life of 7 others - were taken on a

tragic flight back from Panama to Buenos Aires. The plane overhaul took

one day longer in Panama than expected. The Commander would now arrive

home too late to participate in the new Commanding General’s

Reception. To compensate for the loss of that day, the Commander

changed his mind, during flight, when he neared Antofagasta, Chile. He

contacted Antofagasta radio and requested to divert from their filed

Flight Plan. He had decided to fly a VFR shortcut across a more rugged area

of the Andes, instead of spending the night at Antofagasta and next day

taking the southern Mendoza Pass they normally took. This would save

one day and get him back to Buenos Aires just in time to participate in

the new Commanding General’s Reception. Unfortunately that decision

sealed their fate. After a second Antofagasta transmission, the plane was

never heard from again.

Air search parties spotted the wreckage the next day - on a plateau in

the rugged Andes mountains at 16,500 ft. altitude, near Salta,

Argentina. Ground searchers left Salta and traveled a six-hour journey

by Jeep and then by mule-back ride into the mountains. The Commander

had been unable to clear a 17,130 ft. blocking ridge and crashed while attempting to turn around. All 8

persons aboard were killed.

Charley was only 29 years old at the time. However, he had

accomplished more in his 29 years than many individuals do in a

lifetime. Though he is no longer physically with us, his legacy lives

on. Those men of his 3rd Attack Group in New Guinea are true heroes.

In a nation presently groping to find role models, the stories of these

brave soldiers of WWII need to be told and retold – and passed from

generation to generation. May the stories of their courage and

sacrifice forever linger and be an inspiration to others.

The Mayo Family

Submitted by Lou Mayo Ladson